JONATHAN BRODY: Molecules & Music

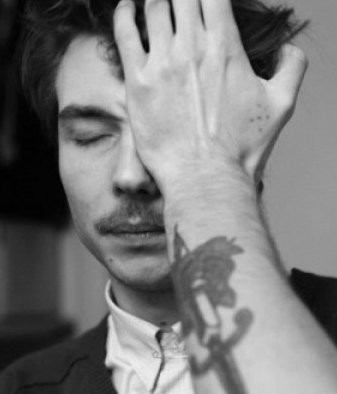

JONATHAN BRODY is a molecular biologist and world-renowned cancer researcher at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. The Department of Surgery at Jefferson holds a unique position in the history of American medicine. Many of the field’s most gifted visionaries have been faculty members.

Dr. Brody focuses his research on finding innovative therapeutic strategies for his patients. He recently collaborated with his former music teacher, Anthony Holland who had the idea to investigate killing pancreatic cancer cells with sound waves. The research began promisingly, but has since ended without quantitative results. Dr. Brody continues to seek creative solutions for the treatment of cancer. We were fascinated by his out of the box thinking and his penchant for the arts, so we jumped at the chance to ask him a few questions.

Interview by Melissa Unger

What initially led you to realize the importance of looking outside the scientific community when exploring cures?

Well, as far as pancreatic cancer is concerned, really patient outcomes have not drastically changed in decades. So we need to push the envelope a little. That said, a lot of really good conventional research is being done in this field, but in order to provide advancement to the community, alternative work also fills a void and a need. A past mentor once said to me that there are always hundreds of great questions, you just need to find the five amazing ones to focus on. Part of picking the amazing ones are picking ones that are completely different and studying something that no one else in the world is studying—this is the aspect of my job that I love and makes me so excited to come to work each day. Additionally, another mentor always use to say to me if the project isn’t a little risky and doesn’t make you very nervous then its not a worthwhile journey to go on.

If your innovative research eventually proves correct, and finds a cure outside of traditional medicine, it would have a huge impact on how cancer is treated- leading to an intellectual and economic upheaval in the field. Has your community been supportive of your ‘out of the box’ thinking?

If we can make some breakthroughs I think this could change the economy and focus of the field and that would be great. The work we are doing with RNA stability, a stress response protein, modulating the immune system, and giving tumors diphtheria toxin DNA are all very innovative and exciting. We have gotten this work accepted at some high impact journals in cancer research but still I don’t think we are on a lot of people’s radar screen.

Throughout history, scientific pioneers like Nikola Tesla for instance, were often met with disdain when presenting ideas that were too far ahead of their time for the mainstream to accept. How do you manage to trust your instincts, push forward with your vision and cope with skeptics?

As for how to trust my instincts, that comes down to experience and wisdom (like in any field)…after awhile you make choices based on your knowledge and experience and you hope you are making the correct creative choices. It is truly a similar process to that of an artist, the difference is science and nature do not take creative license and you have to chip away at the sculpture of what you are working on in order to get the correct piece/statue. For instance, if a rock band comes out with an album that is outside their genre and audience’s taste, music listeners could argue whether this was a good experiment or not, for a scientist we don’t have that luxury—its either authentic or not. To me this is why trying to make discoveries in science is always more beautiful and more difficult than creating art or any other field.

As an adult, do you have a creative outlet?

I have a drum set in my apartment and sometimes play with the medical students here and was in a band when I trained at Johns Hopkins called The Tom Kelly Band (named after a famous molecular biologist who taught me and is at the same time a great guy and character). But my other big active passion outside of the lab is watching and playing basketball.

Do you use the creative part of your mind and/or your imagination when you are doing research?

It’s hard to see and depict where connections and creativity come from. A lot of inspiration comes from the research community, patients, and most importantly my colleagues and the students and young people that are training and working in my laboratory. As a musician, I think learning the scales is very important for then soloing in a song and when you get really good like the great jazz musicians you can go in and out of a key signature when you solo and know one will notice. I think that it’s the same premise with science, you need to have strong knowledge base before you free form or solo in the laboratory with ideas and techniques.

On a more personal note, I’m curious about your childhood. Did you always want to be a scientist, or were you also attracted to the arts?

Well, my dad is a psychiatrist and my mom is a high school teacher who teaches courses like psychological themes in literature (like Shakespeare and Freud, etc). I also went to college on a music scholarship. I was always into artsy, music stuff but never felt satisfied with the abstract aspect of it—it was too open ended (my brother is an art historian who teaches at the Parsons New School in NYC). So in one regard, I’ve always been around that atmosphere, but whether its personally or about the universe, I’ve always been interested in the truth…and I think the most satisfying and most precise way to go after the truth in this universe is by studying science.

That is a very interesting response, because you seem to see science and art as mutually exclusive. You ‘chose’ science as means to get to the ‘truth’, yet your ideas, insight and inspiration come from something else, something creative and rather intangible… I propose that one cannot exist without the other and that advancement relies on a combination of ‘art’ and science. Wouldn’t it be great to eventually erase that rift and end the age-old battle of art vs. science and just accept that they work best in tandem?

I think you make a great point here and I don’t by any means try to add fertilizer to this rift. Some of my best friends are fictional writers, filmmakers, and artists. In fact, one of the women I dated in the past who I was most connected with was a artist-painter. And on the other side, I find that scientists can be too narrow-minded and creatively conservative in their thoughts and focus. I’m not going to say I make it my mission to fuse both art and science in my career or work, but I certainly think I take more of an artist’s approach to what I am doing more than a straightforward scientist approach. My mentor and I wrote an article entitled, “Herd Mentality in the Biomedical Sciences” voicing our concern about the very fact that science in general can follow fads and groupthink. I think art in its purest form follows the creative and open-minded spirit—and I believe there is a strong place and need for this type of thought in science. When pay lines at the NIH are less than 10% its worrisome to think what type of ‘herd’ science would get funded over an out of the box idea that could be pioneering and revolutionary to the field. So to answer your question, both in the past and currently I think the best discoveries rely on the tandem of art and science, but I guess I would wish that science was just considered more of an ‘art’ both in and outside the field. Of note and an example from the artist side, I recently saw Eddie Vedder play a solo show without the band Pearl Jam. His stage-hands and himself (at the end of the show) were wearing lab white coats and I heard him reference to the show as ‘an experiment (without the band)’ in the past. I think this approach and thought process both in art and science is the type of mentality we need in order to get something done and make real, innovative discoveries. Mr. Vedder’s acceptance of experimenting with his music and challenging his creativity to play without a band is the type of experimentation and challenge we as scientists need to put on to ourselves everyday.

M.U. 2012

To view more photos by Eileen Jantz please visit: www.eileenjantzphoto.com

Published: November 21st, 2012