And the rain, soft cannot wash it all away

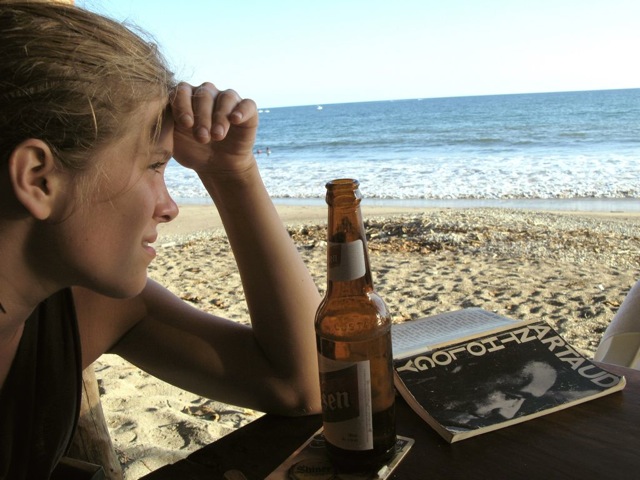

We invited our friend & artist Jan Baracz to honor his beloved Sabrina Seelig in our magazine. Seymour is proud to provide a platform for Sabrina’s brilliant creative voice. Approaching the 5th anniversary of Sabrina’s death, it is with profound respect that we share her story and offer you her words.

On the morning of May 30th, 2007 Sabrina Seelig, a 22 year old artist, writer and student went to her neighborhood hospital in Brooklyn. She was a perfectly healthy young woman; but the previous night she had been up all night translating Latin for a project at Hunter College where she was studying Classics. Early the next day, she felt dizzy, and decided to call an ambulance to take her to The Wykoff Heights Medical Center to seek medical care. Her family and friends tried to locate her for the next eight hours: we found her that evening in the emergency room, in a coma. She was sedated and never regained consciousness. Sabrina Seelig was pronounced dead on June 5, 2007, ten days before her 23rd birthday. Even today, 5 years after this tragedy, the passage of time has not dulled our sharp sense of shock.

Today Sabrina’s charismatic vitality and the powerful resonance of her writing remain with us in the rich legacy of her journals, plays, poems, stories and novel, continuing to bring together those who knew her, and those who learned about her after her death. To those of us who knew her and loved her, Sabrina lives on, inseparable from her art.

To read Sabrina’s full biography, click: here.

To read more of Sabrina Seelig’s work, please visit: www.sabrinaseelig.net

The Time of the Darkest Color

by Sabrina Seelig

I had a friend when I was young. After childhood and before the rest of it: suspended, still. When I was beginning to understand the curled edges of things, but before they had curled around my wrists and chest, along the length of my thighs: before. She had matted black hair and she was my sister’s. A lisp. She called through my door, she asked me to come out and I wouldn’t. It was the beginning of a certain cowardice. She knocked again and I stayed there, still, listening, a pointing dog. Breathing and waiting, as if I had been caught at something, as if she had threatened to break down the door. My sister was out there, but she liked Isabel for her oddness; her big pants belted out of the belt loops like a bum’s and sometimes as dirty. I didn’t know if I liked Isabel at all. She smiled and asked me questions and that thrust a leaden lump against my throat. She knocked on my door when all I wanted to do was open it. Not a savior. When I wouldn’t answer, she went away.

When we were in school, I might see her in the hallway with my sister and she wouldn’t see me. Someone would be sneering at her, or at me, the whole thing dim and smelling low, the formaldehyde fumes from the science room where they were dissecting fetal pigs. She walked with her shoulders to the wind, gustless, with her head tucked like she was making a break and snarled her lips to show her small, square teeth.

Once, when I was eating lunch from a molded plastic tray, she sat across from me and my stomach became hot and the muscles dropped and I was glad for the first time since having to sit in that lunchroom. My sister came to join her, asking me how I was and pretending that I hadn’t been a merry corpse for years. Isabel looked at me and said “Terrible, isn’t it?” before laughing out of the side of her mouth: flecks of tuna, chocolate milk. She would be dead before she turned twenty-three.

Every day, I took the bus home. I walked down the road and counted things, looked at the pattern of trees. I listened to the woodpeckers chattering against their ant-rich trees and the birds that sang indifferently until I was home and the house was empty and I looked around and the wood of the floors sang and sang. I ate. I made large pots of tea that I drank until they turned cold. I watched the few channels of T.V. that reached all the way out there for hours. Fuzzy talk shows and sitcoms that were never funny enough. Once, when it rained all of a sudden, hard, in the very early spring, I took off my clothes and ran out into it. I filled a glass bottle full of rainwater and never told anyone: too precious, but terribly so, like lost virginity, because it was also ugly. I stayed up late, and how I managed that, I don’t know. I should have been anxious and grateful to sleep, but that was the time of the darkest color. I wrote things that I never finished, drank more tea, read novels that I didn’t understand, but they played with the fringes of things that I did. When I woke up on the weekends sometimes Isabel would be there in the driveway with a blonde haired boy, and they would go away with my sister and I would look out my window, to see how they talked to each other. I thought about going with them. The thing that was not true about that thought. Even if it had been, what a choke, a clasped fist.

Walking in and out of that road. Walking out the road in the morning with the air of winter sucking at my wrists and face, how it didn’t make you think of death, but it did make you think of survival. Surviving, I went forward. My sister and I watched T.V. together when she came home after school and she controlled the channels. She stuck out her legs on the couch and flinched them away when my feet touched hers.

I had friends in the school I left the year before. I worried their names and faces, rubbing the angles and turns of them until they were featureless. I worried my body, my belly and thighs. I went to the woods to hide. I tried to write in my closet, and sometimes it worked. Isabel sang into my keyhole a couple of times, but then I didn’t see her.

By the middle of the years I knew someone and she said, “Your sister’s friends with Isabel?” And I said yes, wondering if that was a good thing. She told me that someone had died, she told me how. She told me that and I saw Isabel’s head on the headrest of a truck, rolling back from a violence that had turned the thing so far it had come back upright. I saw too much and I was relieved that I didn’t know anything when she was singing through my keyhole. I would have tried to touch her fingers through the slot. “She was in a coma for weeks. And he got charged with manslaughter. The prison.” It was across the street from the school. I curled my fingers back up inside my palm. Isabel’s lisp like tiny weights on odd corners of her tongue. I didn’t want to know: her fingers closer and also stuck fast behind a sheet of something transparent and impenetrable. She had never been there, anyway. I would never admit that I wanted her like a lover who had died, especially because I had never had anything of the kind. After that, I watched her from the keyhole instead. She forgot about me until I was forced from my bedroom to the bathroom and she called me from my sister’s room: the smell of smoke I wasn’t supposed to smell. I never quite believed she wanted anything, or when I did, I always thought my sister didn’t want it enough for both of us.

One morning, when it had begun to be warm and school was almost over, I was waiting for the bus at the end of the road and my sister was there, too. In a beaten red car, two people drove up to us and stopped and it was Isabel and she was with the blonde-haired friend. There was also a guy laying in the backseat, which gutted me for the moment before he sat up groggily and my sister pushed me in ahead of her, next to the kid. They smoked and talked and laughed and fell silent and stopped for gas and asked me questions they already knew the answers to and Isabel laughed as well and stuck her feet out the window, trying to flip other cars off with her middle toe and pushed the seat-back down into my sister’s lap and she was yelling and pushing it back. I didn’t move because I didn’t want my arm to touch my sister: it would be embarrassing for us both for her to flinch away in front of all these yelling, smoking people. I got out at the school and went inside. I read the Age of Innocence in study hall, I sat on the floor at the ten-minute break. I looked at people going down the hall, looked to the end of it, at those small people and how much better they were down there than in front of me.

Isabel had walked past the door when we’d entered it. She walked in front of a train in Italy when she was twenty-two. The house from back then had been sold, the wooden floors quiet, now. Now, keyholes, a waft of smoke, the smell of bodies, I waited. Breathing slow and quiet, listening for whether she would go away.

© Sabrina Seelig

Published: May 8th, 2012