LIMINAL LANGUAGE: An exploration of final words by Lisa Smartt

The Final Words Project is a fascinating and powerful exploration into the nature of consciousness after death as well as the linguistic patterns that can be found in the language of the dying.

Founded by LISA SMARTT and RAYMOND MOODY in 2014, this intriguing project collects stories and transcripts of final conversations at end of life. At Seymour we are interested in exploring altered states of consciousness of all sorts from the flow state that artists often encounter in their practice to states experienced via plant medicine. Here, Lisa Smartt – poet and linguist – takes us even further into altered states and explains her project’s objectives, as well as discussing her own personal connection with its origins, developments and findings. finalwordsproject.org

Interview by Melissa Unger

The Final Words Project is a fascinating and intriguing project. Tell us about the moment that triggered it.

On my 53rd birthday, the phone rang before sunrise. Who would call this early? I thought. Something is not right.

“It’s mom. Dad’s in the hospital. “

That morning and those words marked the beginning of a three-week period in which my father died from complications related to radiation treatment he was receiving for prostate cancer. I was at his bedside for many hours during those weeks, and as I sat beside him it was as if a portal opened, and as it did I discovered a new language, rich with metaphor and “nonsense” that spilled from my father’s lips.

My mother explained by phone what happened the night before:

My father, a Ph.D. psychologist, walked out the front door at midnight in his underwear onto one of Berkeley’s busiest avenues. When the police found him sitting at an intersection trembling with cold, he explained, “Tonight is the big exhibition, and I am bringing boxes to my wife’s art gallery for the show. I am having trouble finding the art gallery. Do you know where the big exhibition is going to be?”

They shook their heads with pity as they helped him into the police car. There were no boxes in his hands. There was no art exhibition.

The big exhibition my father talked about was merely a metaphor—and I would soon discover that metaphor is common at end of life. It was a metaphor based on the 56 years he lovingly carried my mother’s art work to the various galleries where she showed her work over the years.

He was telling those who listened to him, as he spoke a language veiled in the symbol of the art show, that a major occurrence was on its way.

Using the symbols of the big art show, he was letting us know: pay attention because something major is happening. He was getting ready to die. But at the time, my family members did not know that this kind of figurative language is common in the words of the dying. We dismissed my father’s utterances as mere “word salad.”

Trained as a linguist, I felt compelled to write down all that my father said in his dying days and to study it with the curiosity and care of a scientist. As I did, I began to notice patterns in the unintelligible language that he was speaking and an abundance of metaphors and figurative language.

It was as if I were stepping into another dimension, the kind of dream-like world conjured up by mystics and poets. While grieving his loss, I also felt I witnessed something remarkable as I transcribed his words between the worlds.

Once I witnessed these changes in my father’s speech, I was gripped by a curiosity that has led me to the pursuit of understanding final words.

The language of the dying is a relatively uncharted area. All of us are standing together on this remarkable frontier.

We were drawn to your project in large part due to its lucid and systematic approach to this delicate and polarizing subject. Please tell us a bit about your specific goals and approach.

My specific goals are to (a) better understand what happens to consciousness and cognitive processing at end of life by better understanding end-of-life language (b) to offer up tools for loved ones and healthcare providers so that more compassionate and meaningful conversations can take place as people are dying.

There has been a kind of artificial divide between the sciences and spirituality. For me, that divide makes no sense at all.

Systematic study allows us to uncover the sacred patterns in everything around us. As a student of linguistics, I was provided tools for analyzing and categorizing the patterns of language and to stand in wonder of the ways languages vary and also share certain universals.

Raymond Moody, my mentor and research associate, has determined there is a kind of nonsense taboo. That is, language that is not fully intelligible is frightening and is often quickly dismissed.

However, as we study the language of end of life, we are finding that unintelligible language has its own patterns. Raymond developed a typology that identifies 70 kinds of nonsense.

The unintelligible is as much a product of the divine as the intelligible. Often what is incomprehensible to us becomes new knowledge when studied carefully.

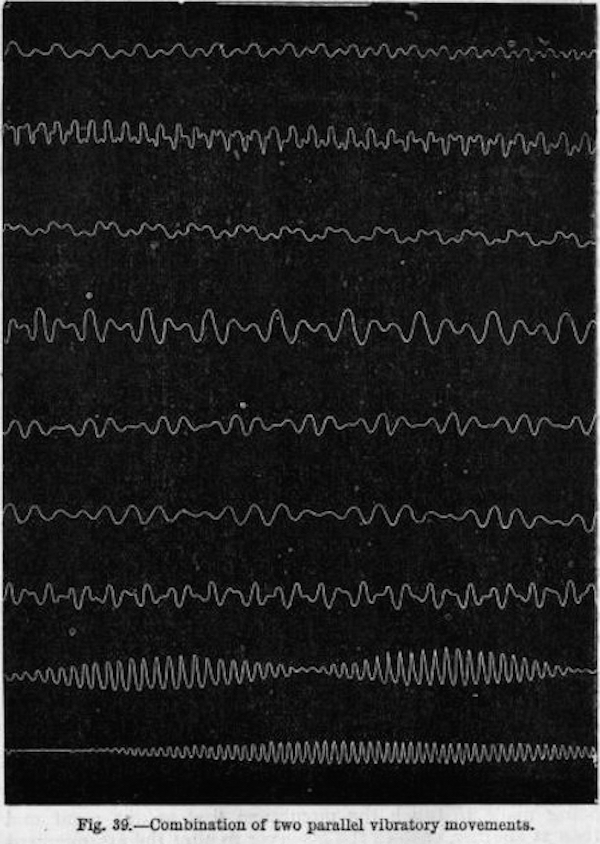

I find the patterns that we are uncovering in the unintelligible utterances of end of life completely divine in their organization. That is, what appears to us as being nonsensical is beginning to fall into patterns and has an inherent organization which has gone, until now, completely un-studied or un-detected.

In the same regard, there are patterns in the symbols and metaphors that emerge at end of life that speak of journeys to be taken, vehicles awaiting, big dances, poker games and golf tournaments awaiting the arrival of the person who is dying. Or in my father’s case, there was the metaphor that was so closely connected to the narrative of his life of the big art show.

I stand in awe as I examine the language of end of life, particularly, the language that is considered “nonsensical.” We are slowly and surely finding categories in the unintelligible language—such as a preponderance of paradoxical speech, non-referential speech and shifts in how prepositions are used.

One of the cornerstones of your project is that speech can illuminate consciousness. Let’s start off with how the utterances of the dying can provide insights into brain function (& vice versa).

There are patterns in unintelligible and figurative speech at end of life. Among the kinds of “nonsensical” conversation that appear most frequently are references to predeceased friends and family members coming to take people “home” or “away.”

Conversations take place that appear to be between worlds, between the dying and the dead. This is not just reported by a handful of “New agers” but by doctors and healthcare workers. Even the most skeptical of physicians will tell you that once they hear that patients are seeing pre-deceased loved ones, then death is clearly imminent. These kinds of visitations and conversations occur across meds and diagnoses—and even when there are no meds.

Deathbed visitations and their conversations have been documented by a handful of researchers past and present but have not really made it into the mainstream conversation about death and dying.

There is also an abundance of use of non-referential pronouns, “This is quite interesting. I have never done this before,” my father explained to his secretary days before he died. Or Roger Ebert’s,”This is all an elaborate hoax. It is all an illusion.” The appearance of the non-referential use of the pronouns this and that and it’s is very common in the language of the dying.

It is as if reference is being made to something but we are not privy to what it is. The language implies there is a larger context, but of course, most of us who are living and at the bedside of the dying are not fully aware of that larger context.

You’ve noted that as we die brain centers associated with literal and linear language lose their dominance. This has even led to the coining of a new language: “trans-sense.” Please give us a better understanding of this liminal “language”.

This liminal language has markers that are not evident in ordinary healthy living language. We see an increase in symbolic or metaphoric language and in nonsensical and paradoxical constructions such as, “Introductory offer on goods and services… store is closing…” We also see repetition, such as Steve Jobs’s “Oh Wow! Oh Wow! Oh Wow!” Repetition appears with much greater frequency in the language of the dying. And it’s hard not to ask, “Why?”

Raymond Moody suggests that in fiction, nonsensical terms such as “shaazam,” and “abracadabra,” “open sesame” have a cross-dimensional quality. When they are spoken, doors open, dimensions shift; one can see this in religious services as well. Certain words, especially nonsense ones, with interesting pronunciations, have the ability to open doors and shift realities for us. While these examples are drawn from fiction, there seems to be some basis in reality that the language between states is often nonsensical. One can even look at the liminal language of teenagers in which lots of nonsensical and new language is formed as a way to mark their territory outside of the mainstream narrative.

Nonsensical language plays a very dynamic function in language in its role of being outside the main narrative.

This “trans-sense” language seems to evolve into a state “transcendental awareness”. Please explain and perhaps share some examples of this surprising state.

Paradoxical language is common both when people describe NDEs and when people are dying. One example of this is in the language of blind people who have had near-death experiences.

Kenneth Ring reports in his book Mindsight that 80% of his blind subjects reported being able to see when they had their NDE’s. Now in ordinary speech, this is technically considered nonsense; it is a self-contradiction or a paradox. How is it possible that a blind person can see? Ring describes a transcendental awareness that occurs in near-death experiences; this awareness involves a sense that we do not yet understand. It makes it possible that the blind “see” things when they experience out of body and near-death experiences.

This sentence “The blind can see.” is technically nonsense, but one might ask, then: Is this nonsense, or perhaps a new sense. Perhaps there are ways of experiencing the world that are so far outside our usual perspective that to describe it sounds purely nonsensical or paradoxical. Other paradoxical phrases of those who have had near-death experiences include: “I have never felt as alive as when I was dead,” or “There was no language in the afterlife but they communicated in a way that seemed to speak to my soul.”

These kinds of paradoxical constructions appear also in the language of the dying but are often even more enigmatic.

I like to use Dr. Will Taegel’s term trans-sense when speaking about the paradoxical and other nonsensical constructions of the language of the dying because nonsense is often used pejoratively. I like the term trans-sense as it makes people think twice about language and how language might function at times.

Many final words such as those of Steve Jobs and Roger Ebert imply as concretely as has ever been stated the presence of “something else” after life. What is your current perspective and understanding of what this “something else” might be?

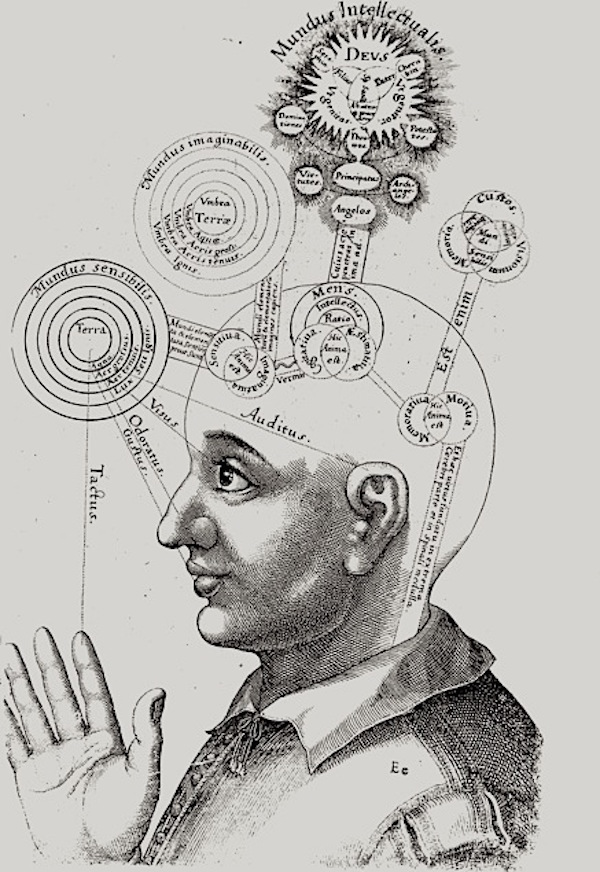

My only imagined sense is that there is a world not beyond us but beside us that vibrates at a higher frequency, beyond a frequency associated with bodies and dense matter.

You’ve quite beautifully described your father’s final words as an “emergence of metaphors and figurative language … like stepping into another dimension, the kind of dream-like world conjured up by mystics and poets.” In your opinion, is this altered state similar to that which can be experienced during the creative process?

Yes, I do. These are all fascinating kinds of language that reveal another kind of reality, tapping into something different, and creativity is nurtured by seeing the world differently. It is through a new lens, that new vision is born. In this way, the language is– I believe– the language of creation. And ironically, this highly creative language emerges in the dying process.

Scientific American had an interesting article about brain imaging that explained that metaphoric language engages both right and left brain hemispheres. There are indications from other research that nonsense engages regions of the right hemisphere. I have come to think that perhaps certain parts of the brain degrade as we die; then others begin to predominate. It is possibly those more associated with what we think of as “creativity / right hemispheric functions” predominate.

How has your approach to your own life changed since you embarked on this project?

I have a very different feeling about death and dying. The more I have researched, the more I am convinced that something exists beyond or besides what we know of in this 5 sense dimension. I am not sure what it is, but I know that just as poetry and dreams offer us a rich landscape with multiple meanings and expanded understanding, the language of the dying has offered me an enlarged sense of the sacred. Also through my interviews and reading about near death experiences, I have so little fear left about dying. The stories of near-death experiences are completely compelling.

There are moments I think to myself, “Well, maybe it’s that in those moments before we die, we have these transcendent moments just to make death easier for us.”

However, colleague Dr. Erica Goldblatt Hyatt said to me one day: “What would be the evolutionary advantage of transcendent experience at end of life; why if this is merely a biological directive, would it exist at end of life? Wouldn’t nature “favor” painful death so that it would be avoided at all costs? What survival advantage is there in a transcendent experience as we die?” It seems there has to be some reason for it beyond the merely physical as it does not really make sense in that context.

The more I research final words and the language of the afterlife, the more I am convinced that consciousness survives or transforms after death—and if not, my research indicates that the transition to dying does not have to be something to be feared. It seems we enter an altered and even magical state –and the language we speak as we die offers some window into this new dimension; whether this dimension is fleeting or represents the afterlife, I am not certain.

I strongly hope that those who are reading this will bring an open heart and mind to their conversations with their dying beloveds, and approach the language with curiosity and wonder. Instead of saying, “Daddy you are not making sense!” I hope that people will say, “Wow, Dad that is so fascinating! Please share more with me.”

We can only know more by hearing the stories and reading the transcripts that loved ones share with us. If anyone reading this has final words to share—whether they make sense or don’t—please go to the “Share Your Story” tab of the Final Words Project website. We are collecting stories and final words in all languages:

www.finalwordsproject.org/share-your-story

Published: October 15th, 2015